by Susan Schoenian [1]

Sheep and Goats Western Maryland Research and Education Center

From 1998 to 2002, I served as a technical advisor to the Maryland Department of Agriculture’s Caribbean Hair Sheep Trade Initiative, visiting Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Dominican Republic, and the British Virgin Islands. I judged the National Sheep and Goat Show in the Dominican Republic on three occasions. This article is based on my observations and experiences in these countries.

********************************************

Sheep raising is a traditional enterprise in many parts of the Caribbean. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, there are approximately 1.4 million sheep in the Caribbean. Cuba has the largest national sheep flock, followed by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Some of the smaller islands such as Barbados, have large sheep populations relative to their geographic size. There are considerably more goats than sheep in the Caribbean, though some islands have larger sheep populations.

As with other countries and geographic regions, various production systems are used in the Caribbean to produce lambs, though there are certain practices that are popular among many producers. These include year-round and accelerated lambing, early weaning, and confinement rearing. Ewes in the Caribbean are able to produce lambs throughout the year, since there is not much variation in photo period (length of day) in countries that are close to the equator as compared to the U.S. Instead, nutrition is the limiting factor to sheep reproduction, as most countries experience a wet and dry season and tropical forages tend to lack the nutrition of temperate forages. Protein is in especially short supply and hay and concentrates are expensive to purchase.

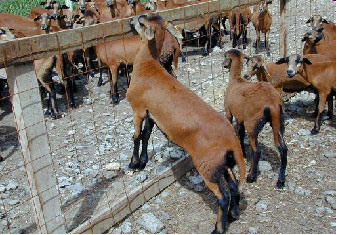

Sheep in the Caribbean are often raised in confinement, often on slatted floors and raised decks. There are many reasons for this: internal parasites, security, and the high cost of land. Forages are fed as green chop in what is typically called a “cut and carry” system. Small farms cut forages by hand, whereas larger farms mechanically harvest the forage. Due to the high costs of concentrates, the feeding of by-products is quite common, e.g. poultry litter, cull bananas, sugar cane molasses, and citrus by-products. It is also common to fatten lambs in feed lots. In Barbados, there is a central feed lot where producers can bring their lambs. Lambs are slaughtered at lighter weights as compared to the U.S. and lambs are generally much leaner. Some of the better farms will market lambs weighing over 90 lbs. Prices for lambs tends to be higher than in the U.S.

Marketing is a limiting factor to sheep production in the Caribbean. Most of the small islands lack adequate processing facilities, and thus cannot market lamb to the potentially lucrative tourist trade. As a result, most small ruminant production is consumed by the local population. Local demand is usually greater for goat meat, though sheep meat tends to be preferred by tourists.

Due to the climate, the vast majority of sheep raised in the Caribbean are hair sheep, as hair sheep are better able to withstand the rigors of extreme heat, humidity, and internal parasites as compared to wooled sheep. While many sheep breeds are raised in the Caribbean, the Barbados Blackbelly is probably the most populous. Other breeds include the (Cuban) Pelibüey, West African, and St. Croix.

In Barbados, the island where the Barbados Blackbelly evolved, probably from sheep brought over on slave ships, the breed is truly a “national treasure.” No other breed of sheep is raised on this tiny island which is the eastern most in the Caribbean chain. In fact, Barbados is the only Caribbean country I visited where local lamb was available on the menu of some restaurants. It was listed as “local Barbados Blackbelly” lamb, and it was delicious!

Barbados Blackbelly sheep are favored in the Caribbean, not only because of their adaptability to the environment, but due to the reproductive efficiency. I consider them to be one of the most reproductive efficient breeds of sheep in the world. Barbados Blackbelly ewes and rams reach puberty at an early age. With adequate nutrition, they produce lots of twins and triplets. They readily breed out-of-season. In the Caribbean, it is common for a ewe to drop three lamb crops in two years. Rams are aggressive breeders.

However, I found the Barbados Blackbelly breed in the Caribbean to differ significantly from the breed in the U.S. and from the Texas Barbado. The differences can be explained by crossbreeding. When Blackbellies were brought to the United States, many were crossed with the Rambouillet or wild Mouflon, to create a “trophy” animal for game ranches. Texas, in particular, has a lot of these “Barbado” sheep.

In the Caribbean, Barbados Blackbelly rams do not have horns. Only small scurs or diminutive horns are permitted. Barbados Blackbellies in the Caribbean have a more calm disposition than those raised in the states. Many of the Barbados Blackbelly sheep I have seen in the Caribbean are larger than those I have seen in the U.S. The best animals I saw were on the island of Trinidad, the southern most island in the Caribbean chain. Efforts are currently underway to try to import Barbados Blackbelly semen from there to the United States. Of course, animal health regulations make this a difficult and lengthy undertaking.

My very first experience with the Barbados Blackbelly breed was as an undergraduate student at Virginia Tech where I helped lamb out a bunch of Dorset x Barbados Blackbelly crossbred ewes. Though these ewes tended to be a bit “flighty,” many people agree that they are one of the most productive ewes you can have in a commercial lamb production system. Virginia Tech still uses Barbados Blackbelly ewes for crossbreeding to compare hair sheep to wool sheep and perhaps one day the breed will be part of a new composite hair sheep breed.

[1] Sheep and Goat Specialist, Western Maryland Research & Education Center, University of Maryland Cooperative Extension, sschoen@umd.edu, www.sheepandgoat.com

Reprinted from BBSAI Newsletter, December, 2003.

Copyright 2003 BBSAI. All rights reserved.