David R. Notter

Dept. of Animal and Poultry Sciences, Virginia Tech

The hair sheep breeds of the Caribbean are a significant genetic resource for development of “easy-care” sheep types. High levels of ewe and lamb vigor, resistance to internal parasites, and freedom from shearing can reduce labor and management costs associated with the ewe flock, while crossbreeding with rams of meat breeds can maintain growth and muscling in the crossbred lambs. Further, among the Caribbean hair breeds, the Barbados Blackbelly is unique in combining these easy-care characteristics with high levels of prolificacy.

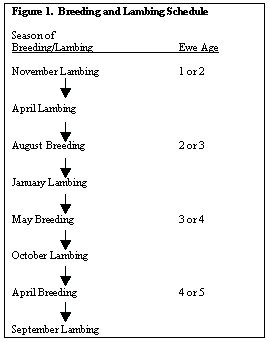

The experiment described below was designed to compare Barbados Blackbelly x Dorset crossbred ewes to ewes of several other maternal types including the Dorset, Finnsheep, and Dorset x Finnsheep cross. Ewes were born in 2 years and evaluated in several different breeding seasons. Young (one- and two-year-old) ewes were first mated in November to lamb in April. The ewes were then rebred in August to lamb in January, and finally, as adults, were bred in May to lamb in October and then in April to lamb in September (Figure 1).

Thus over the course of the study, ewes of the different types were evaluated both as young ewes in traditional fall and late summer matings and as adult ewes in spring breeding. Ewes were bred to blackfaced rams for the first two matings but to Dorset rams for the last two out-of-season matings. Lambs were weaned at 40 to 50 d of age to facilitate rebreeding of their dams.

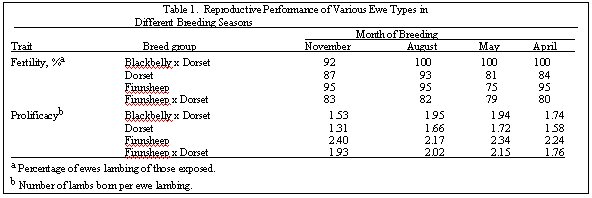

The reproductive performance of the various ewe types is shown in Table 1. The fertility of young Blackbelly x Dorset crossbred ewes in November breeding averaged 92% and was similar to that of Finnsheep ewes. However, in older ewes, fertility of Blackbelly x Dorset ewes was consistently 100%, even in spring. The Dorset and Finnsheep ewes were similar in fertility to Blackbelly x Dorset ewes in August but the Blackbelly crosses were superior in fertility to other breed groups in May breeding and were superior to all breed groups except the Finnsheep in April breeding.

Prolificacy (lambs born per ewe lambing) was consistently highest for Finnsheep ewes. Blackbelly x Dorset ewes were also less prolific than Finnsheep x Dorset crosses at first lambing but were consistently more prolific than Dorset ewes and were only slightly less prolific than Finnsheep x Dorset ewes after the first lambing.

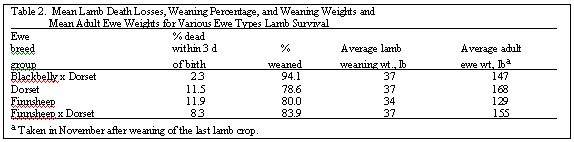

Across all lambing seasons, average death losses within 3 days of lambing were much lower for lambs from Blackbelly x Dorset ewes than for lambs from ewes of other breed groups (Table 2). The proportion of lambs weaned was correspondingly higher for Blackbelly x Dorset ewes, although values for Finnsheep ewes may be biased somewhat since most triplet and quadruplet lambs were reared artificially and not credited to their dams.

Average weaning weights (Table 2) were similar for lambs out of ewes of the various types. Lambs out of Blackbelly x Dorset ewes were heavier than lambs out of Finnsheep ewes and similar to those produced by Dorset and Finnsheep x Dorset ewes.

The mean adult ewe weight of 147 pounds for Blackbelly x Dorset ewes was somewhat less than that of Finnsheep x Dorset ewes (Table 2) but was acceptable for crossbred commercial ewes.

Our Blackbelly x Dorset ewes all produced substantial, kempy fleeces that required shearing but had no commercial value. Breeders should thus expect to have to shear hair x wool crossbred ewes. Backcrossing of these crossbred ewes to hair sheep or selection within advanced generations of crossbred animals will likely be required to produce animals that do not have to be sheared.

The Blackbelly x Dorset ewes produced in this study were very productive animals. They were superior to ewes of all other types in fertility in spring matings, lamb survival, and percentage of lambs weaned; were similar to Finnsheep x Dorset ewes in prolificacy; and, when mated to blackfaced or Dorset rams, produced lambs that were comparable in weaning weight to lambs produced by ewes of the other types. These Blackbelly x Dorset ewes could thus have been useful in a wide range of production systems.

The rams used to produce these ewes were of the Texas “Barbado” type, with large, flaring horns similar to those of the Rambouillet. Thus, despite having a predominantly hair coat, they should not be considered as equivalent to the polled Barbados Blackbelly animals found in the Caribbean. The relative merits and extent of common ancestry of these different Blackbelly types remains the subject of some debate. Greater access to animals from the Caribbean and the comparison of imported animals with existing U.S. Blackbelly populations would provide useful information. However, the performance of the crossbred ewes in this study clearly demonstrates that the Texas Barbado sheep are a valuable genetic resource in their own right and may make important independent contributions to the development of easy-care sheep populations.

Reprinted from BBSAI Newsletter, April, 2004.

Copyright 2004 BBSAI. All rights reserved.